what did the colosseum in rome look like — then and now

You’re here because you’re asking what did the Colosseum in Rome look like in its prime—and how that compares to what you see today. Short answer: the Colosseum was a bright, elegant, white-gold oval wrapped in three rings of arches and columns, topped by a flat attic with sockets for a giant velarium (retractable awning). Inside, polished marble seats circled a sand-covered wooden arena above hidden machinery and lifts. Today you still see the powerful skeleton, but much of the marble, seating, and the full arena floor are gone.

The quick snapshot (dimensions, feel, colors)

If you could step into 80 CE on the day of dedication, this is what you’d notice in seconds:

- Size & shape: an ellipse about 189 m × 156 m (620 ft × 513 ft), rising to roughly 48–50 m (157–165 ft). It seated around 50,000 people.

- Skin: creamy travertine blocks on the outside; warm tones in sun, cooler tones in shade.

- Style: three stacked arcades framed by engaged columns—Doric (or Tuscan) at the bottom, Ionic in the middle, Corinthian on the third level—then a solid attic with small windows and awning masts.

- Shade: a huge velarium spread from the top ring—think ship rigging—pulled by trained sailors.

- Floor: a wooden deck covered in sand (harena), later pierced by trapdoors and lifts from the underground hypogeum.

- Finishings: colored plaster, painted details, and statues set in many archways added drama.

Outside, up close: stone, arches, and statues

Stand on the paving stones by the Rome Metro stop and walk toward the façade. In the 1st century, the stone would have looked tight-jointed and crisp, with metal clamps tying blocks together. The travertine exterior wasn’t rough—many surfaces were dressed smooth, some even with a subtle sheen from wear and limewash.

Each of the three open tiers was a ring of arches (80 per level). Columns were not free-standing; they were engaged into the wall—a classic Roman way to layer style onto strong concrete structure. The order stack (Doric → Ionic → Corinthian) made the building appear lighter as it rose. Between some arches, niches held statues of gods, emperors, and trophies, so the shell felt like a living stage set even before games began. Dimensions and the column orders are laid out clearly by Encyclopaedia Britannica, a solid reference for the building’s form and size.

Up top was the attic story with stone corbels (little brackets) and sockets for the velarium masts. Picture giant tent poles leaning out over the oval: when canvas spread across, the sun softened, wind fluttered the fabric, and the whole arena took on a sailing-ship ambience.

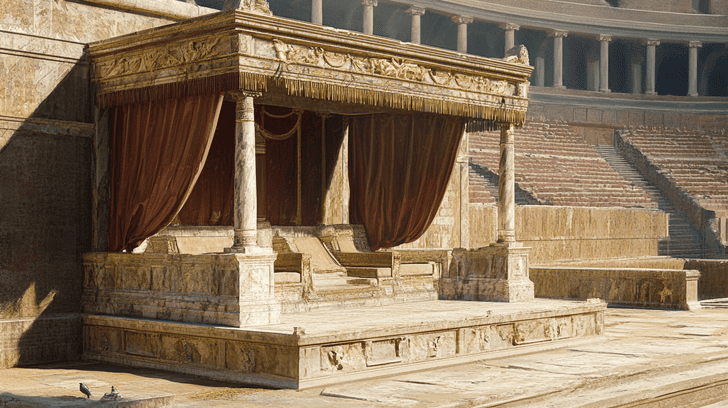

Inside the bowl: seating, sightlines, and sound

Walk through one of the numbered arches and you’d enter the vomitoria—efficient corridors that fanned crowds to their seats in minutes. Social order decided where you sat: senators and VIPs close to the arena on marble benches with name labels; citizens higher; women and the poor on the upper tiers. The bowl linework was clean—curved flights of steps, low walls, and radial aisles that kept the view open. With 50,000 voices and a brass band, the sound bounced but didn’t muddle; the Romans were masters of crowd flow and acoustics.

Look down: the arena was wood planks, topped with sand to soak blood and give gladiators traction. Under that (especially after Domitian’s works) lay the hypogeum: tunnels, cages, winches, and elevators. From here, animals and scenery could appear as if by magic, lifting through trapdoors so the crowd gasped in unison.

The arena floor: scenery and stage tricks

Because you asked what it looked like, imagine the stagecraft. Painted backdrops, movable trees, and mechanical lifts allowed the editor (show producer) to switch scenes fast—savannah one minute, mythic forest the next. The sand wasn’t a single color; fresh layers were raked in during breaks, so the floor could change tone through the day, from pale straw to reddish where it mixed with dust and blood. Festival days added banners and bunting to the ring wall and emperor’s box, so the tone was more carnival than ruin.

Color matters: was the Colosseum white?

Mostly light stone, yes—but not monotone. Many surfaces had pigmented plaster or painted architectural details, and the crowd added color: dyed tunics, soldiers’ shields, shaded velarium strips. Even the statues in the arcades likely had color traces, just like other classical sculpture across the empire. (Roman public architecture often mixed marble, stucco, and paint to create a richer effect than bare stone alone.)

The engineering skeleton behind the beauty

What gave the Colosseum its distinctive look was beauty on a backbone:

- Concrete & vaults: A lattice of barrel and groin vaults held up the seating. This made the building freestanding (not cut into a hillside), which was unusual for amphitheaters and allowed Rome to place it at the heart of the city.

- Materials mix: Travertine for the frame and façade, tufa for inner walls, and Roman concrete for the bowl and vaults. The mix reads visually: crisp outside, practical inside.

- Rigging ring: The velarium masts and ropes were a visual signature. Hundreds of sailors (yes, sailors) managed it—because those were the people trained for big canvas.

The setting: what the Colosseum looked like in its neighborhood

In antiquity the arena stood by the Palatine Hill, replacing a lake from Nero’s palace. Streets and porticoes around it framed processions and food stalls. On a festival day you’d see banners across the street canyons, hawkers selling figs and flatbread, and streams of people moving in waves. The Parco archeologico del Colosseo (the site authority) notes how the amphitheater became the public heartbeat of Rome’s spectacles—exactly the civic role its Flavian builders intended.

Then vs. now: how the look changed over 2,000 years

What you see today is the survivor of earthquakes, stone-robbers, and time:

- Lost skin: Much marble seating and revetment was removed in the Middle Ages and Renaissance for churches and palaces, leaving the concrete bones visible.

- Broken ring: A chunk of the outer wall is missing—earthquakes did that—so you read the internal structure like a cross-section.

- Arena exposed: After the wooden floor vanished, the hypogeum was left open. From above, it looks like a maze of walls and pits.

- Modern additions: new walkways, protective railings, and spot-lighting at night. The glow at dusk gives back a hint of that ancient golden hue.

Micro-tour: how to see the original look on your visit

- Walk the perimeter: Start at the intact arcades to admire the column order stack. Once you’ve spotted Doric → Ionic → Corinthian, you’ll never unsee it.

- Scan the attic: Find the corbels for the velarium; imagine the canvas fanning out.

- Look for clamps: On broken edges you can spot metal clamp scars where decorative skin once tied together.

- Inside the stands: Picture marble benches and colored stucco instead of bare stone.

- Over the void: When you stare into the hypogeum, mentally cover it with fresh sand and a painted set—that flips your brain to the original stage.

People also ask (straight answers)

Was the Colosseum pure white marble?

No. The façade was travertine (a creamy limestone), with marble used for seating and decorative elements. Surfaces had paint and stucco, so the effect was warmer and more varied than a modern white ruin.

Did the Colosseum have a roof?

Not a solid roof, but a retractable awning called the velarium. Sailors operated rigging from the top ring to shade spectators. Visually, this was a huge part of its identity on show days.

A tiny story to lock the image in your mind

Imagine you’ve got a ticket from a friendly fruit seller. You pass under a numbered arch, cool air from shaded corridors on your face. You climb two flights and step into blinding sun + silk-shadow from the stretched velarium. The bowl is pearl and straw—stone and sand. Trumpets blast; a painted pine forest rises from the floor by hidden lifts. A senator waves a purple-trimmed hem at the emperor’s box; kids point at bronze-rimmed shields glinting in the light. That’s the look of the Colosseum: order, color, movement, bound to an elegant shell of arches.

FAQ (quick, useful, and to the point)

How big was the Colosseum compared to a modern stadium?

The footprint (189 m × 156 m) is similar to today’s large arenas, but the height and open-air design with a fabric awning make it feel lighter. Seating was roughly 50,000, like a mid-sized football venue.

Why are parts missing?

Earthquakes and stone-quarrying for later buildings stripped the outer ring and interior marble, exposing the concrete skeleton you see today.

Who finished the building?

Built by the Flavian emperors: begun by Vespasian, dedicated by Titus (80 CE), and completed with the top story under Domitian (82 CE). That timeline also helps explain when underground works expanded.

Where exactly is it in Rome?

Just east of the Palatine Hill, in the core archaeological area managed by the Parco archeologico del Colosseo (which includes the Roman Forum and Palatine).

Could they flood the arena for naval battles?

Sources mention mock sea fights early on; later the hypogeum made large-scale flooding impractical. Visually, the arena most often looked like sand over wood with scenery, not a water basin.

Wrap-up you can quote (featured-snippet ready)

What did the Colosseum in Rome look like?

A travertine-clad oval of three arched tiers (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian) crowned by a flat attic and awning masts, enclosing a marble-seated bowl around a sand-covered wooden arena. On show days it added color, canvas shade, statues, and scenery, so the vibe was lively and sun-washed—not the bare stone ruin you see now. Core facts on its size, orders, and awning come from Encyclopaedia Britannica and the site authority, the Parco archeologico del Colosseo.